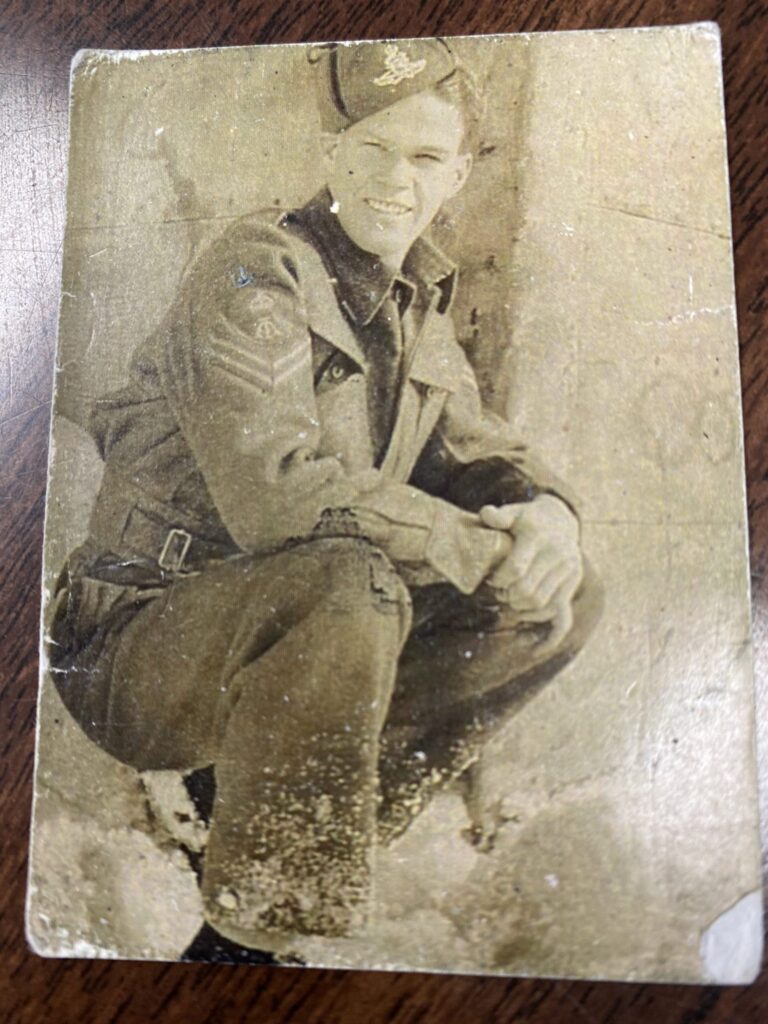

While he will never tell you this, Haliburton resident Harold ‘Rowdy’ Rowden is the very definition of a war hero.

Serving with the 3rd Division of the 13th Field Regiment during the Second World War, Rowden was there the day members of the Canadian military went where no Allied soldiers had gone before, pushing the Nazis out of their beach-front strongholds and sending them into retreat.

The Normandy landings, and in particular the Canadian affront on Juno Beach, have long been considered the catalyst for the Allies’ eventual victory. The sacrifices of the men who stormed the beach on June 6, 1944 will be honoured Nov. 11 as part of our Remembrance Day rituals. Rowden was 19 when he stepped on the ship in Portsmouth, England bound for France.

He remembers that daunting journey – the eerie silence among usually rambunctious troops, the sickening sway of the boat, the dread that set in as soon as land came into view. “Everything was on fire,” Rowden said of the scene that greeted him when the landing ramp dropped. Within seconds, he lost dozens of comrades, friends he had come to know and love during his years of deployment in the UK.

As a dispatch rider, Rowden’s orders were to collect messages from one point and deliver them to another. Equipped with a Norton motorcycle, he was one of the lucky few to escape Juno Beach unscathed.

D-Day was Rowden’s first overseas mission. He had spent years training at various sites across Canada and the UK since signing up for the war effort at 15. Still, nothing could have prepared him for the horrors he would face that day, and the many that followed. “If anybody says they weren’t scared, then they weren’t there,” Rowden said. “It wasn’t nice. I had never seen anything like that before. The Germans were up there picking us off. The beach was covered [with dead bodies].”

After safely getting out of the water, Rowden found a tank he could strap his bike to and crawl on top of. He was carried away from the action. Once settled he got to work on delivering messages between command and gunners.

His orders were often top secret. Just days after the landings, Rowden’s regiment came under direct attack. His unit was bombed while stationed in a small town called Courseulles-sur-Mer. Four of his comrades were killed, while his commanding officer was badly wounded.

Knocked unconscious, Rowden eventually came to and, noticing a gaping laceration in the officer’s neck, did what he could to patch him up. Equipped with only a field dressing he had stuffed into his helmet, Rowden covered the wound and applied pressure until medics arrived. “I guess they told me that I saved his life,” Rowden said.

Years later, once the war was over and having returned home, Rowden and his then wife bumped into the officer again on the main street in Orillia. His wife knew the man from school so went over to say hello. “She gave him a bit of a hug, and then he turned to me and said ‘you look familiar.’ I thought ‘it can’t be,’ but it turned out it was. I said ‘you old fart, you’re still alive!’ At the time, I didn’t know if he had lived or not.”

After recovering from a serious concussion sustained at Courseulles-surMer, Rowden participated in the Battle for Caen. During intense enemy shelling, he was hit by a blast that threw him into the air and against a truck. His left leg was damaged so badly doctors initially wanted to amputate.

He also injured his back and right leg. He was transported back to England where he spent months recovering in a hospital in Watford, near London, before being put on a ship to Canada. His service was over. Rowden spent several months recovering at a military hospital in Kingston.

After months of rehab, he re-entered the workforce, became a truck driver, married and had nine children, including three sets of twins.

Rowden has received eight medals, including France’s highest honour, the rank of Knight of the French National Order of the Legion of Honour. Consequently, Rowden should be referred to as Sir Rowden. Even when talking about his experiences, Rowden displays a tremendous amount of humility, saying that, deep down, he doesn’t believe his actions merit any special attention or recognition.

“I am proud, but you would have done the same things as I did back then. Anyone would. You don’t have to be a hero to patch someone up when they’re hurt. The way I see it, if you see a dog down in the ditch, you help it,” Rowden said. “And the medal … I’m doing alright right now, I lived a life. That should have been given to one of the boys that lost his life.”

Rowden said Remembrance Day is a time for careful reflection. “I’m proud, but I’m sad. I was only a kid back then, but the whole Canadian army was pretty well just kids. So many people died on both [sides]. Many times, it was kill or be killed, but I took no glory in any of that. I lost a lot of friends over there. Remembrance Day is a time I can remember them.”