Haliburton County has released its roadmap for creating a community climate change action plan. In broad terms, the initiative has three stages.

The first is to develop a plan to reduce corporate emissions and next, adapt County and municipal operations for a warming world. The last stage, developing a community plan, is just getting underway.

Ads in local media encourage the public and stakeholders to sign up to join an advisory committee, focused on chatting about recommendations and next steps. “This will focus both on reducing emissions from our broader community as well as adapting,” said Climate Change Coordinator Korey McKay. “This isn’t the only group that will provide input, [but] this will give preliminary input into strategies, goals and actions.”

Apart from advisory committee meetings, she guessed online surveys might be the main way to engage the wider community. While COP26 saw global leaders discuss national climate agreements, The Highlands needs to brace for a warming world, say local groups like Environment Haliburton! and Concerned Citizens of Haliburton County.

They organized a rally on Nov.5, where 15 people gathered to ask questions and raise concerns about climate change on the front steps of the County’s offices. Warden Liz Danielsen, Dysart Coun. John Smith, climate change coordinator Korey McKay and CAO Mike Rutter attended the rally. “Local leaders play a vital role in turning pledges into action,” Carolynn Coburn of EH! and CCHC said at the gathering. Danielsen, addressing the crowd, said “we really are in a bad spot when it comes to climate. We need to make a change here in Haliburton.”

The County has spent the past year and a half, with the help of McKay, educating municipal councils on how climate change will impact the Highlands, and how the Highlands’ emissions are contributing to the crisis.

Assessing the damage

During Minden Hills’ Nov. 11 council meeting, councillors listened as McKay explained the County’s plan.

She has a lot of practice: attending Zoom meetings for all four municipalities, explaining the process of collecting greenhouse gas emissions information and outlining ways all four townships and the County could cut back. Strategies for reducing the County’sfootprint hinge on McKay’s community greenhouse gas inventory, the first of its kind to be conducted in the County.

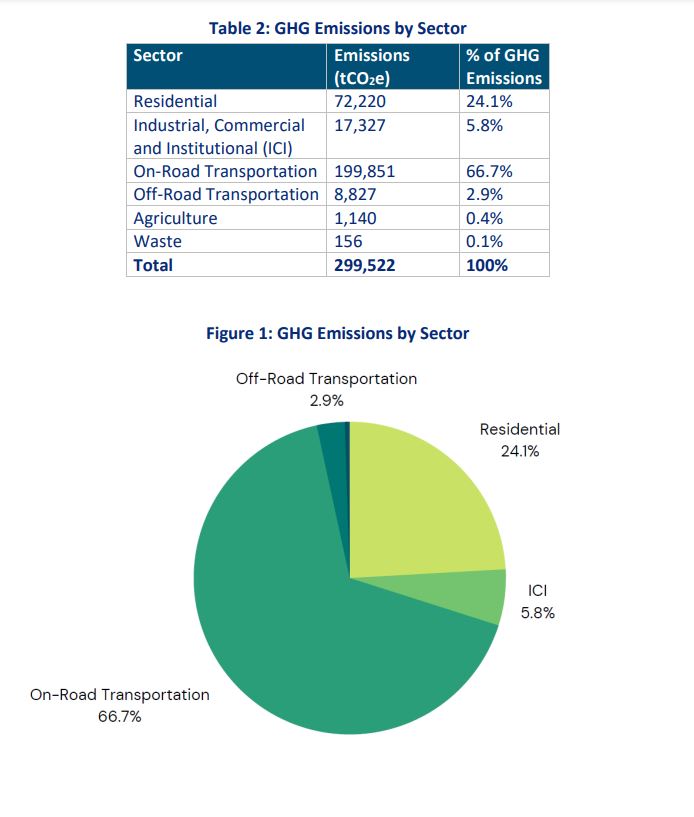

A greenhouse gas inventory is an estimation of the emissions that Haliburton produces: 299,522 tonnes of carbon dioxide in 2019, out of Canada’s total output of about 582 million. Per capita emissions in the county is 7.6 tonnes a year per person; lower than the provincial average of 11.2. Driving is the largest emitter in Haliburton, accounting for an estimated 199,851 tonnes of carbon dioxide, a figure obtained by calculating average road usage in areas around the county. All lower-tier governments, as well as the County, are on board with a plan to reduce their corporate emissions below the 2018 baseline by 30 per cent by 2030.

“My work is really to investigate the impacts locally, and what we contribute locally. Seeing those numbers really helps to localize the issue,” said McKay. “In tandem with creating a plan is also having an educational piece; why climate change is an issue and what are the co-benefits that we can realize when we implement a climate change plan.”

There’s broad scientific consensus that warming temperatures will impact life in Haliburton. As McKay’s report states, annual precipitation will increase, along with the likelihood of flooding. In 2013, floods in Minden caused an estimated $571,000 in private residential damages.

Frequent winter storms could prove disastrous in a county with many hard-to access roads and isolated communities with little or no cell phone reception.

That’s a future which many in the County fear. “There were people stranded for weeks…” in parts of Ontario and Quebec, said Coburn, talking about an ice storm in 1998 that caused 34 deaths in Quebec and Ontario. “In situations like that, we’re going to have to depend on people within walking distance, our neighbours.”

For Coburn, the issue of climate is local: if municipalities and counties don’t step up, federal initiatives will flounder.

The Europe-based Climate Alliance, a network of cities fighting climate change, said municipal action can lay the foundation of change. “Municipalities can engage their residents to contribute to the fight against climate change in their everyday lives, be it in terms of consumption patterns, lifestyle choices or ways of doing business,” they write on their home page. Municipalities can also chart development and urban expansion.

Near Haliburton, Grass Lake cottagers are rallying to protect a private stretch of wetlands that could be turned into condominiums. “We want to protect this land and, ultimately, protect Grass Lake,” organizer Carolyn Langdon said in a prior interview.

Wetlands such as the Dysart property play a vital role in fighting rising temperatures. The County is home to part of the Highlands Corridor of provincially significant wetlands, zones that act as carbon sinks and are also shown to help mitigate flooding.

While blanket wetland protections fall outside municipal jurisdiction, conservationists are taking action.

Spearheaded by the Haliburton Highlands Land Trust (HHLT), there’s a growing coalition of private property owners signing up to protect areas of wetlands on their properties.

“Natural solutions can help to mitigate impacts like flooding and drought, conserve biodiversity, protect ecosystem services, connect landscapes and capture and store carbon,” said HHLT chair Shelley Hunt in September. “Canada has committed to protecting 30 per cent of our landscape by 2030. In Ontario, only 10.7 per cent of our landscape is currently protected.”

Decision with ‘an eye to climate’

“My question is: why the reluctance to declare a climate emergency?” EH! President Susan Hay asked Warden Liz Danielsen at the rally.

In 2019 council voted against the declaration, with some councillors saying at the time it was premature given they had no road map for handling the issue. “I really feel that the message that conveys to the community is not a good look,” Hay said.

Danielsen replied: “I can’t disagree with you, but I also cannot answer for the rest of County council. It’s a group decision and it’s not mine to make.”

Haliburton’s neighbour, Muskoka, recently declared a climate emergency in tandem with Gravenhurst and Huntsville. They also implemented a 50 per cent reduction goal by 2030. That’s a steeper climate change goal than the Highlands.

“We set targets we know we can accomplish,” said Danielsen. “I think we’re on the right track.” Coburn said she sees the County taking the issue “more seriously than in the past. However, she added, “I’d like to see more talk about it, I’d like to see them making decisions with an eye to a changing climate.”

That’s what Lauren Phillips would like to see too. The Haliburton Farmers Market coordinator moved to the County in 2020.

She said climate action “starts from the ground up.” Despite forecasts of a difficult climate future, Phillips said she wants to be able to tell future generations “I tried my best. I did my best to have a voice and make it heard.”

A rotting issue

“It breaks my heart,” Oliver Zielke said loudly, his voice ringing out over the crowd facing Danielsen, Rutter, McKay and Smith. He was asking about composting. Or, specifically, why no municipality within the County offers composting services to commercial facilities, multi-residential buildings or individual residents.

While a waste audit, scheduled in Dysart and Minden Hills this year, will provide a clearer picture, a large amount of compostable waste ends up in landfills.

In Dysart alone, a 2019 staff report estimated 667 to 1,111 metric tonnes of residential food waste ended up in the dump. Townships have developed composting initiatives, like the FoodCycler indoor composting unit program that Dysart and Algonquin Highlands recently endorsed. While landfills only account for about five per cent of Haliburton’s emissions, Zielke pointed to the long distances Haliburton waste travels after it’s pitched. For example, Dysart’s garbage is sent to Orillia, then transferred to Watford, nearly 500 kilometers from Haliburton.

In an email, Dysart environmental coordinator John Watson said this is because the Dysart landfills don’t have “environmental safeguards” in place to mitigate methane gases produced by waste.

A path forward

The majority of Canadians believe climate change is a present threat, according to a Research Co. poll. The Highlands’ recent shoreline preservation bylaw exposed fractures in how the community wants to deal with it.

For Leora Berman of The Land Between, the shoreline preservation draft process was a good first step in protecting lakes and wildlife habitats as temperatures rise: what’s needed, she said, is more community involvement.

“The county has shown leadership recently with the shoreline bylaw,” she said. “The issue is they haven’t done the consultation and education necessary. If they do the consultation and education and consider the constituents partners with them, they’ll do a great job.”

While the County hosted two virtual openhouses on the shoreline bylaw, anger from the bylaw’s opponents and misinformation spread primarily on Facebook has dismayed members of council. “The divisiveness and infighting amongst friends and neighbours, I’ve never seen anything like it,” Algonquin Highlands mayor Carol Moffatt said at an Oct. 27 meeting.

Warden Liz Danielsen and Terry Moore of EH! reported they’ve received threats and verbal abuse in relation to the bylaw. Even throughout EH! And CCHC’s other events throughout the year, Coburn said many in the County seem misinformed about climate issues or quick to dismiss activists.

“We’re all regular people, there are some people who call us extremists,” Coburn told the crowd. “We care about nature and the future of humanity.”