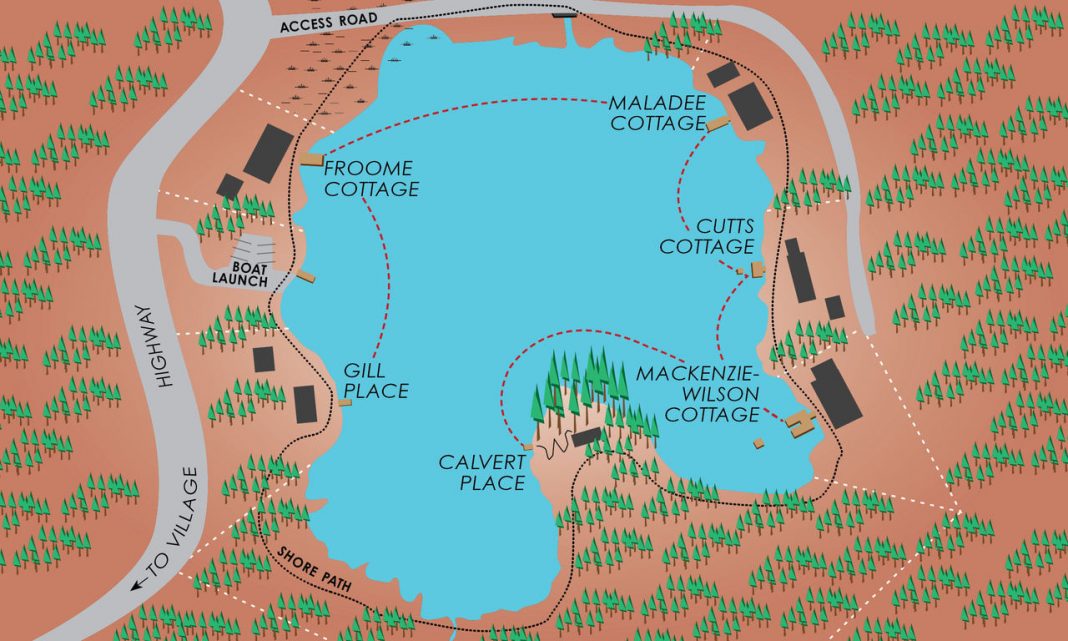

After interviewing with the Froomes, Detective Harry Harp and Constable Terry Becker rowed south following the shoreline. They had left the two women inside their sealed, lakeside home with instructions to remain there until further notice.

Becker said, “Since Mimi Froome admitted to untying the boat, Grace’s story holds up. She slept in the woods.”

“But she still had the opportunity to kill her mother. We can’t rule her out,” Harp said.

As much as I’d like to, he thought.

The late afternoon sun cast a slippery haze over the water and insects skated in circles around the rowboat. In the distance, a dock appeared and Harp noticed a man standing on it. The man was Frank Gill.

After tying the boat, he led Harp and Becker up a short path to his small, woodsided cabin. Inside, Harp was greeted with the smell of mould and fried bacon. A smoke-stained fireplace took centre stage in the living room across from a small, grimy kitchen. For decor, Gill had pinned up posters of fishermen in action, a map of Spruce County and an out-of-date calendar.

There was another picture, too – a painting of a woman.

Gill arranged a couple of kitchen chairs and invited the men to sit down, then sat in the chair across from them – the one with a clear view of the Calvert point.

“I didn’t like leaving Grace alone. I sure hope she’s OK. ‘Course, I’ve been watching but I’ve seen no sign from the Calvert place. Not as yet.”

The three men sat in silence for a moment. Then Becker broke it. “Nice place you got here, Frank.”

He shrugged. “She’s old and nearly in the ground, much like myself. I reckon we’ll both go about the same time.”

Harp watched him turn his attention to the point. He asked, “How long have you known the Calverts?”

“Since the summer of ’61.” Gill leaned back, clearly on his favourite subject. “Ida was 16 and I was fishing on the lake that day – but by the end of the afternoon, it was me that got hooked.” He grinned at them then gestured at the portrait across the room. “Her picture was painted about that time.” He stared at it for a moment before continuing. “She came up with her parents every summer and then when she was 24, they died in an accident. Left everything to her, of course, so she had no worries – except grief. That’s when she moved up here.” He looked over at the point again.

Harp had the feeling he spent his days looking at the Calvert point.

“I think she wanted to hold on to the memory of her parents, the happy summers, her childhood. Anyway, she decided to stay, year round.”

Becker looked incredulous. “Is the Calvert place even insulated?”

Gill shook his head. “Nope. But it didn’t matter. She was determined. Anyway, the two of us got prepared for winter as best we could. I tell you, I was never happier – even though I knew it was foolhardy. See, we were together then. That is, until everything fell apart.”

Harp asked, “How so?”

“She got pregnant.”

Becker’s eyes widened then slowly narrowed. He blurted out, “Grace?”

The old man nodded. “I wanted to marry Ida. Make it all proper, you know? But she wouldn’t hear of it. And that’s when she went a bit off. Turned into a recluse. A hermit. Wouldn’t hardly go anywhere. So I set up on this side of the lake to be of help. Taking young Grace to school and back, running errands, you name it.” He sighed bitterly. “Been doing that all my life. Been a loyal servant to Ida Calvert.”

A fly bounced against the window trying to escape.

“Love sure does make a man a damn fool.” He scratched the stubble on his chin. “I think of that summer day back in ’61 and sometimes I wish I went fishing on another lake.”

Harp said slowly. “Does Grace know you’re her father?”

Gill shook his head and whispered, “Ida swore me to secrecy.” The old man leaned forward in his chair, muscles tense, eyes fixed on Harp’s.

The detective stared at him for a moment, then stood up and crossed to the painting hanging on the opposite wall. The artist had captured a smiling young Ida Calvert, her face tilted to the side like she had a secret she was considering whether or not to reveal. Her eyes were sparkling emeralds and she had wavy chestnut hair. Harp was suddenly struck by the realization that he’d seen that wavy hair earlier in the day—but it had been gray and fanned out over a blood soaked pillow.

Becker said, “What were you doing last night, Frank? Between ten and midnight?”

Gill leaped forward. “You think I did it? You think I murdered the only women I’d lay down my life for?” He jumped to his feet, his voice rising. “Sure, I loved her – and I hated her! Sure, she destroyed my life. But I would never ever do anything to hurt her, you hear me?” Using the back of his hand, he wiped spittle from his lower lip, turned and walked out of the cabin.

Silence filled the void—except for the creak of the screen door swinging free of its frame.

A gust of air ruffled the old calendar. Harp clocked the date: 1961. Since then, the old man’s life had been held in a kind of love struck limbo.

He’s right about one thing, Harp thought. Love makes a man a damn fool.

A couple of minutes later, the two men walked to the dock where Gill stood brooding.

“Look,” he said, turning suddenly. “I was here last night! And what are you wasting your time with me? There’s a killer out there!” He took a step towards Harp and in a second, the man’s hand gripped Harp’s forearm and yanked him close. “Useless city cop,” he hissed.

Becker quickly stepped between them. “Hey Frank? What’s – that?” He pointed down the lake in an attempt to change the subject.

“Huh?” Gill’s anger evaporated and Harp took the chance to free himself. He looked where Becker was pointing. In the distance a pale shape bobbed against the shore.

“Ida’s boat,” Gill, said finally. “Figured it would turn up somewhere.”

“We’ll get it on our way back,” Harp offered.

“NO!” Gill swung around. “I take care of the Calverts. Always have and always will.”

Back in the rowboat, Harp watched Gill slowly dragging the Calvert boat behind his outboard.

A loyal servant, Harp thought.

“Do you believe his story?” Becker asked.

“Most of it. But you saw the anger in him. It’s enough to make him commit an act of violence.”

“But to the woman he’s loved for 60 years?”

“Loved – and hated.”

On the Calvert dock, Harp saw that the two officers who had inspected the shore path and he hoped they had news.

Becker asked, “So what’s next?”

Harp rolled up the sleeves of his shirt. “Now,” he said, “We play a game. This bunch has been playing with us. Now it’s our turn.”