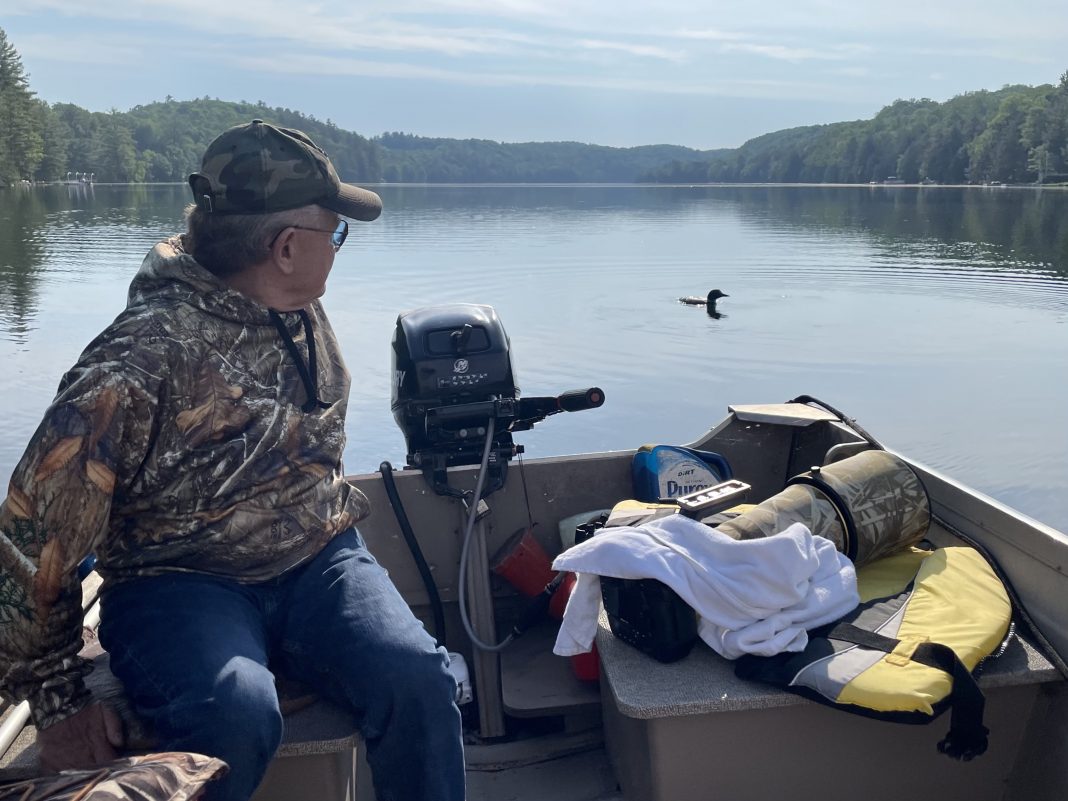

Across Salerno Lake’s calm waters, it’s easy to spot Kevin Pepper.

He’s sporting a camo Blue Jays hat and a big grin; driving a small metal boat with blue pool noodle bumpers; hefting a camera with a camo-covered lens so large you need to hold it in both hands.

Most cottagers on the secluded lake – as well as thousands logging onto Facebook around the world – know exactly why he’s out on the water, at 7 a.m., on a Monday morning.He’s checking on the loons.

Over the years, Pepper has developed a world-wide reputation as a loon photographer, chronicling the lifecycles of Salerno loons through the lens of his camera.

From the moment they land on the lake in the spring until they fly south in the fall, Pepper follows their lives on the lake, snapping thousands of pictures along the way. And he has helped countless others experience the loons too in workshops that, until COVID-19, attracted photographers from Dallas to France.

On an early Monday morning, out on Salerno with The Highlander, Pepper explained how his love of loons began after he built a bunkie on the shores of the lake in 1996. His wife noticed the loons and over time, watching them pass the dock was a morning tradition.

“I would know their morning pass-throughs, and I would make sure I’d be down there when they went by – that’s how it kind of started,” said Pepper.

In 2014, he left a full-time corporate position and began living at the lake nine months a year.

“I drove home from work for the last time on Oct. 31,” Pepper said. “On Nov. 1, I was up in the morning, on my dock, with a cup of coffee, going to photograph loons by myself.”

International tours

I was shocked because I

had never seen a loon

so close to me before.

It was quite an experience.

Nando Tedeschi

“When I say ‘loon up,’ you get your camera up’,” instructed Pepper. That’s what he tells all the tourists who come out to see the loons: the birds are quick, and learning when to snap the shot has earned him his reputation.

He and his nephews had started a tour company that led photography workshops around the globe, but as they got steadily busier, Pepper stepped back to focus on loons and workshops at Salerno.

In his spacious cottage that overlooks the lake, he’d host photographers of all skill levels: from a Nikon brand representative to hobbyists with iPhones.

Some years he would lead up to 25 tours in a season, acting as the cook, cleaner, entertainer and resident photography expert.

Nando Tedeschi is an avid photographer who found Pepper after looking around Canada for the best places to capture loon photos.

“I was shocked because I had never seen a loon so close to me before,” Tedeschi said in a phone interview. “It was quite an experience.”

Since 2015, Tedeschi has been making trips to Salerno to see the loons. He’s become friends with Pepper and recently, he bought a slice of lakefront property with plans to build a cottage.

Tedeschi’s experience on the lake mirrors that of many who hop in Pepper’s boat. After each trip to Salerno, they leave with much more than snapshots.

“A picture is a picture,” said Pepper, hefting his camera in the back of the boat. But the goal from any session he said is to “walk away with a memory.”

Saving the loons

Pepper swivels in the boat, pointing to a large loon that floats nearby. He says he’s learned how to pilot his boat in ways that ensure the loons aren’t threatened or harmed: in fact, he and his cross-lake friend Wendy will spend many weekend afternoons acting as an honour guard: sheltering loons from busy recreational boating traffic as they make their way across the lake to hunt and eat.

“That’s a tribute to Kevin,” said Tedeschi, mentioning how comfortable the loons seem to be with Pepper. “Kevin is passionate about the loons and their safety.”

The loons get to know his boat: one year while two parent loons were fending off attackers, a chick sought shelter right next to Pepper’s prop engine.

“I pride myself on that,” Pepper said. He chats about how many inexperienced – or careless – boaters don’t know how to drive safely around loons; a boat’s wake can damage nests. He’s even seen boats that seem to try and run them down.

While Pepper is a fierce protector of the loons – he won’t tell anyone where their nests are – he loves to share their lives with the lake’s seasonal and year-around residents.

The same loon who took shelter next to Pepper’s boat became a local celebrity. After uploading his photograph to the lake’s Facebook group, the community voted to give him a name.

Ever since, cottagers and lake visitors remember “Rider.” Everyone knew Rider,” Pepper said.

But like loons do every year, Rider became strong enough throughout the summer, and in the fall took flight – seeking warmth in the Carolinas.

In a small notebook, he keeps track of every part of the loon’s lifecycle – they arrived this year for the first time on April 4 at 10:44 a.m. That skillset has transferred into his workshops.

Right out on the water

When guests arrive – often shaken from the drive on the cottage road that snakes over steep hills – he gets them right out on the water to get used to photographing in a boat.

In the morning, they set off as early as 5 a.m. to catch loons in the sunrise glow.

“I tell them to try for the non-postcard shot,” said Pepper. He explains how the details of a loon, like its velvet feathers or the way water flows from its beak, are the reasons he keeps finding new photos to shoot. Each day on the water he usually shoots more than 300 photographs.

And he doesn’t sell them: “It’s my way of giving back,” he said, with a wide grin. He chooses two a day to post on Facebook, to bid the lake goodnight and good morning. Each post receives hundreds of likes, comments and shares – many from people around the globe who follow Salerno loons through Pepper’s lens.

In 2020, the world came to a screeching halt.

Tourists couldn’t come to Haliburton County, and they certainly couldn’t cross borders or stay with Pepper to go out on the loon watch.

Many were frustrated, some even argued they should be allowed to quarantine up at his cottage: “a lot of people didn’t understand,” said Pepper.

His voice is hushed: a loon floats nearby, about 15 feet off the bow. “I’ll be honest,” said Pepper, his eyes on the loon as it floats serenely in the morning sun, “If I could never lead a workshop again, I wouldn’t be too torn up about it.”

Tours and photos have never been the only thing that matters, he said. What matters is the loons – the chance to observe their lives and share them with others.

“I’m still doing what I do,” he said. “So, people can see it, and follow me, and still be part of it.”