By Mabel Brannigan

Merrill Bailey was one of the prisoners of war from Haliburton and this is in Merrill’s own words.

“I joined the RCAF in December, 1940, and my first billet was Manning Pool, The Coliseum Building in the CNE grounds. My next stop was in Kingston on thence back to Toronto to the Eglington Hunt Club buildings on Avenue Road. From there, I was transferred to Malton Airport (now Pearson International Airport) and began my flying training on Tiger Moths with my cousin as instructor. As I was being trained as a bomber pilot, I was sent to Brantford on twin-engine Ansons. It was there that I obtained my wings as a pilot in August 1941.

In the same month, I married Muriel Johnston, and thence overseas, arriving in England on Sept. 1. After training at Wellesbourne, Warwickshire on Wellington bombers, I transferred to Water Beach, converting to four-engine Stirling bombers. From there, I was sent to Oakington (near Cambridge) No. 7 Squadron, a Royal Air Force unit. There, we began our night bombing operations over enemy territory. After several operations, about 19, on July 1, 1942, our luck ran out. We were caught in searchlights over the target with a steady stream of anti-aircraft fire directed our way. Taking frantic evasive action, I managed to escape the target area, although we had taken several hits. One engine was out of commission and the hydraulic system controlling the guns was also a casualty.

Crossing the coast, we sustained another burst of fire. Suspecting a German night fighter, I dived beneath the clouds and proceeded over the North Sea at a low level.

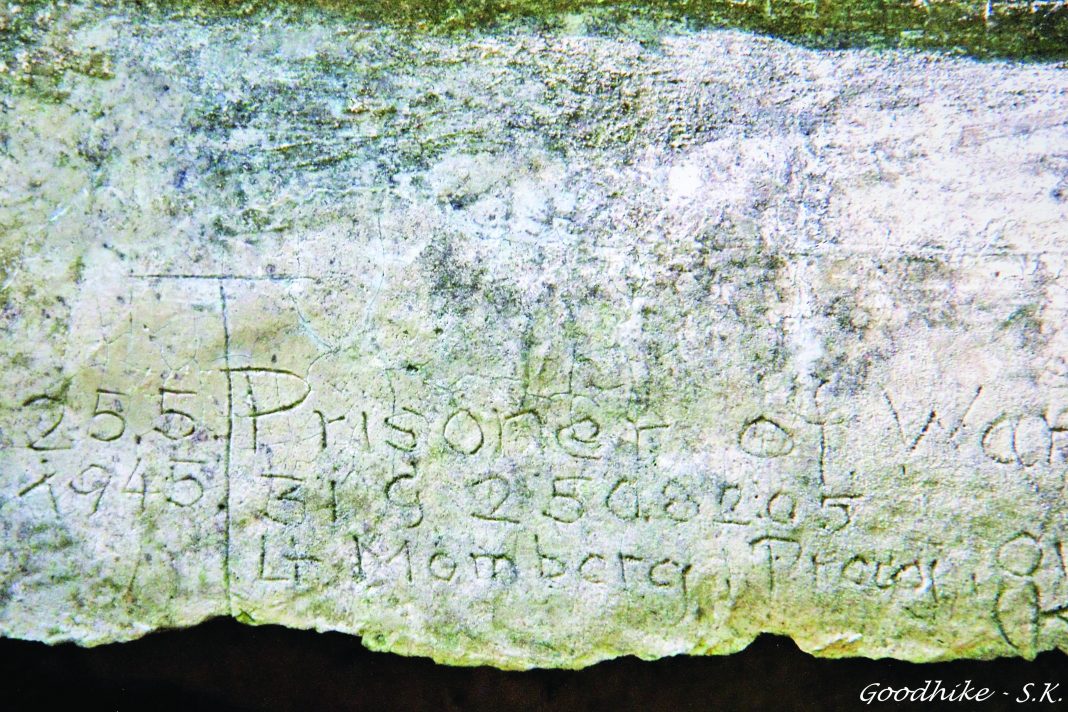

The engineer then reported the gauges indicated a fire and that we were running out of fuel in the wing and that had been hit. The situation was getting desperate when we flew over a German flak ship. They opened fire on us and we crashed into the sea. Two gunners and I survived and the other five crew members were killed. The crew of the flack ship picked the three of us up and we were prisoners of war in Silesea in eastern Germany near the Polish and Czech borders. This area now belongs to Poland.

This camp held thousands of prisoners and many more thousands were away from camp on work parties. Our flying suits and boots were confiscated to be put to use on the Russian front. We were issued wooden clogs, mine being about four sizes too big having to be tied on to keep from falling off. There were 200 in our end with broken window glass, making it cold in the winter. Breakfast was non-existent. Lunch was a few small potatoes. Supper was a hunk of coarse brown bread with the consistency of sawdust. Fortunately, we received a Red Cross food parcel occasionally which we shared. For some time, we were kept in handcuffs. Fleas were our constant companions. And bed buds. We fared better than the Japanese prisoners of war.

From this location in January, 1945, and hearing the guns booming in the distance, the Germans started us on a 600-mile march to keep us from falling into the hands of Russians. Some of us tried to escape. The Nazi sergeant pulled his pistol but just motioned to join the column.

We made our way to England and to New York with Americans. I was too sick to celebrate V.E. Day. I caught a train to Montreal and was hospitalized. My wife came to see me. After my recovery, I rejoined my father in the lumber business at Eagle Lake.”