The sun burned down on the little tin rowboat in the middle of the lake.

Detective Harry Harp dipped his hand in the water and wiped sweat from his face – then removed his tie, folded it and shoved it in his pocket.

Meanwhile, Constable Terry Becker stopped rowing and pulled a stash of energy bars from one of the many compartments in his cargo pants and handed one to Harp. He consumed it in two bites. Becker put the empty wrappers in his pocket.

“Do you believe that stuff about a curse?”

“Not – really. But it’s given Sally Cutts something to blame for her problems. The more things go wrong, the more real the curse must seem.”

Becker took hold of the oars and started rowing again.

“What about the light?”

Harp’s eyes sharpened. “That’s very promising.”

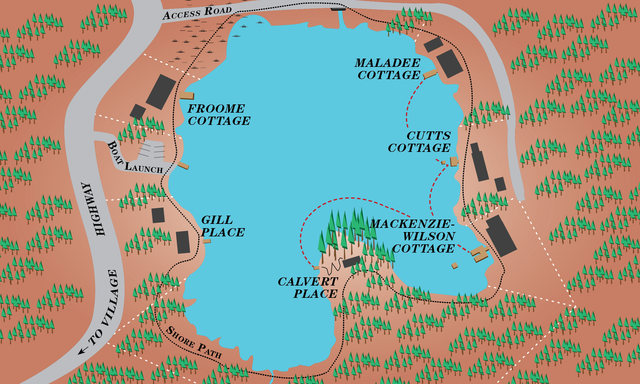

He pulled out his phone, called Spruce County Police Department and, after requesting two officers to inspect the shore path, pocketed the device.

“I have a feeling that path is used a lot more than anyone’s saying.”

Ten minutes later, the two men arrived at the last cottage on the east side of the lake. The Maladee cottage was large and open-concept with a peaked roof and a wall of windows that gave a partial view of the water. The interior was roomy except that every inch of it was occupied. Ornaments, paintings, photos, plaques with amusing sayings printed on them, piles of books, magazines, dirty dishes, wine bottles, including the half empty one in Marc Maladee’s hand.

“Can I interest either of you gentlemen in a glass of fairly decent red?” He was in his mid 50s with wavy brown hair, a beard and a cheerful pair of boozy blue eyes. Harp suspected the other half of the bottle was already inside him. Both men declined and took a seat where they could find space among the debris.

Marie Maladee, ten years younger than her husband and wearing yoga pants and a black top, hovered near the window like she wanted to jump out of it.

“Nice view,” Harp opened with.

Marc plopped down across from the two men, crushing a pile of newspapers.

“You want to know the best view. The Calvert point. Incredible.” He drained his glass. “So? What can we do for you? Must be important. You’re wearing a suit.”

Harp smiled unhappily. He paused then said, “Funny you should mention the Calvert property. We’re here about Ida Calvert.”

“Oh?” “She was murdered last night.” The muscles around Marc Maladee’s mouth twitched but no words came out.

“That’s terrible,” his wife gasped.

“Did you know her?” The woman’s hands flapped around like they were on fire.

“Not really, no. We’re here. They’re there.”

“But you’ve appreciated the view,” Harp pointed out. Marc was up and re-pouring.

“I was on the point once. Just the once.” He smiled and revealed a row of wine-coloured teeth.

Becker said, “What was the reason for your visit?”

“A business matter. Nothing particularly important.” Becker’s glare assured him that it was.

“Tell them, Marc,” Marie said, her hands flapping some more. Marc sat down and smiled resignedly at his audience. “Well, if you must know, I’m quite involved with the community here and I devised a rather ingenious plan to develop a seniors enclave on the lake – a half dozen homes ringing the unused end of the shore, and all interconnected. There would be a main lodge on the point with dining room, library, activities room – and it was to be called Cliffside.” He tossed back a mouthful of wine. “The county was in and we were all set and we even offered Ida guaranteed accommodation in Cliffside – but would she sell? Not on your life.” Marc stood up and took a few unsteady steps towards the counter. Watching him from the other side of the room was his wife and she didn’t look happy. “It couldn’t have been more perfect – for the county, and frankly, for us. And you know what else?” He yanked the cork from a new bottle. “The daughter – Grace Calvert – she was on our side. I honestly don’t know how she stands living with Ida. And they choose to live that miserable Stone Age life.” He sat down again, obviously feeling better with a full glass in hand. “Long story short, Ida wouldn’t budge.” Marc drank deeply and licked the rim of his glass. “That was our last big chance, wasn’t it, darling? But we’ll have another. You’ll see.” He turned to the men. “Marie here’s worried about money but what woman isn’t.”

His wife spun around. “MARC—please,” she cried, her face flushing.

She turned to Harp. “Well? What else?”

“Tell me about last night between 10:00 and midnight?”

She glanced at her husband but he was frowning into his empty glass. She shrugged. “We weren’t here. We arrived this morning so there’s nothing to tell.”

“So where were you last night-?” Becker cut in.

“In the city! Watching TV, O.K?”

“Not O.K. The truth please,” Harp said.

“That is the truth,” Marie Maladee’s eyes narrowed. “And I’m sure you two have other things to do.” She walked towards the door but her husband’s words stopped her.

He slurred, “Cliffside would have made me a very rich man. Would have solved a lot of problems, eh?” He looked around for his wife but she was standing directly behind the sofa where he was sitting. Her sinewy hands tightened into fists then the fists turned to claws that she dug into his shoulders. “Ouch – darling that hurts.” He wriggled out of her grasp. Why is she so tense? Harp wondered. He changed the subject.

“So – how long have you been enjoying cottage life?”

“Very funny,” she sneered.

“But all the signs?” Becker gestured around the room at the plaques declaring, “It’s better at the lake,” “Boat parking only,” “I heart family,” and twenty other similar sayings.

“I get a real kick out of those,” Marc burbled, grinning. Marie folded her arms across her chest and Harp could see tears welling in her eyes.

“Truthfully, it hasn’t been – quite what I imagined.”

Marc tilted his face up to her and whispered, “Everything’s going to be okay, you’ll see.”

Back in the rowboat Harp said, “Did you notice the brand new pack of sparklers on the deck? The receipt was stapled to the bag – bought yesterday. In the village. They were here last night.” Becker whistled.

“Listen to this.” The constable opened his notebook and started reading. “Plastic flowers, stuffed terrier in wicker basket, three broken clocks, carved birds in flight, framed family photos, two old phones, pile of cookbooks, how-to-juggle book, vases with dried flowers, paintings of flowers, pair of ski gloves, pocket dictionary, metal silhouette of a wolf set in a piece of stone, a bear driving a car, a half-full plastic bottle of eye solution, gold mirror, three empty tea candle holders, dirty sock, book about crosswords, map of Corsica, Christmas ornament, tiny closed box.” He shut the notebook. “That was one small shelf. Those people are hoarders.” Harp shrugged off his suit jacket. “And liars.”